Monday, August 29, 2011

Review: The Tale of Despereaux, by Kate DiCamillo

As a parent I think this is a fine book to read to a young child, but I was disappointed by the quality of the story and writing. At age five Calvin was completely capable of understanding the the story as read to him, but would not have been able to read it fluently enough on his own to make it worth while.

Friday, August 26, 2011

Swann in Love, pp. 281-304: Swann at the Verdurins, the satire of the salons

More on the Verdurins' "little group".

Dr. Cottard is a hilarious caricature, completely lacking grace and confidence in any social setting ("he was no more confident of the manner in which he ought to conduct himself in the street, or indeed in life generally, than he was in a drawing-room" p.282), which is almost the opposite of Swann, who is comfortable everywhere.

Saniette has lost favor with the group and is soon to be booted, most likely because he is too deep and has too much of a soul, and thus does not fit in. He "burbles" his speech in a "delightful" way, which is the opposite of the pianist's aunt (the "concierge") who slurs her speech to hide the fact that she knows nothing.

Mme. Verdurin seems to feel more loyalty to (from?) the gifts in her home that came from the "faithful" members of her group. I can only assume that she has some gifts that are from "faithfuls" she has dropped or been dropped by. She even seems to have some sort of a love affair with the fruit carved on one of the chairs. The language is so sensual at that moment that there may be something I'm missing, or we may just be seeing a character trait of Mme. Verdurin. She can have more control over inanimate objects and without risking rejection?

Then Swann and the Sonata in F. Swann has become lazy in life: he refrains from forming opinions or taking part in society and has ceased to have any goal. On p.298 he is described as "morally barren", and he is not even working anymore, as he long ago gave up writing his paper on Vermeer. Now the Sonata in F has given him back some life, "indeed this passion for a phrase of music seemed, for a time, to open up before Swann the possibility of a sort of rejuvenation" (p.296), somewhat like the effect that viewing the three steeples has on young M and his struggle with writer's block.

The Sonata also serves well as an analogy for life and involuntary memory: difficult to assess the first time through, the impressions come on faster than they can be discovered, it leaves the listener the "architecture" by which it can be assessed on a second listen. Much like a second look at life through our memories, and Swann's immediate recollection of the strains in the Sonata bring to mind M's sudden flush of memory upon tasting the Madeleine cake.

"But the notes themselves have vanished before these sensations have developed sufficiently to escape submersion under those which the succeeding or even simultaneous notes have already begun to awaken in us."But while the "little clan" can tell him the name of the work and the composer, they are unable to discuss it beyond that. In reality the composer and piece are fictional, but there has been some discussion about their models.

•••

"And so scarcely had the exquisite sensation which Swann had experienced died away, beofre his memory had furnished him with an immediate transcript, sketchy, it is true, and provisional, which he had been able to glance at while the piece continued, so that, when teh same impression suddenly returned, it was no longer impossible to grasp." (p.295)

Swann seems to have passed the test and been accepted into the little clan, although the Verdurins completely miss his character, believing him to be lacking depth. Mme. Verdurin does tell Odette that she may bring friends like that any time she wishes, though, implying a lack of respect for fidelity, an odd trait for a woman who demands complete loyalty from her "subjects" as she does now from Swann ("provided he doesn't fail us at the last moment." p.304), but this is not the first time we've seen her as the hypocrite.

Satire of the salon. Proust is poking fun at the Salon lifestyle in which he actually took part himself. The the members of the little clan can barely talk to each other, what with the aunt and Saniette mumbling, Mme Verdurin using one figure of speech after another while Cottard does not understand them in the least and misuses them on his own, and Odette sprinkling her speech with English. They neither understand nor care to understand art and music, even if they have their own artist and pianist among them. Since Salons were gatherings intended to inspire artistic endeavors and the exchange of knowledge, the Verdurins make a great satire.

Cool stuff:

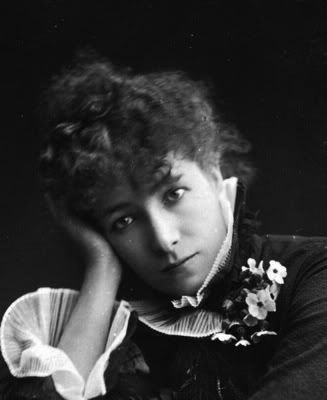

Sarah Bernhardt was a French actress from the 19th century on into the 20th.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Swann in Love, pp.265-282: Swann, Odette, and the Verdurins

I want to love everything about this work, but with this section I am at a loss. Since all the rest of the work so far feels justified, based on the truth of memories and the seeking of them, the transition to this section, which is the retelling of a story once told to our narrator, feels rather awkward to me. The story within a story has never been one of my favorite literary styles or tools, and I can only hope that the remainder of the work does not feel this clumsy.

The Verdurins and their friends are described a little later as being "among the riff-raff of Bohemia" (p.281), which is fitting with their patronage of the artist and pianist, with their acceptance of the "demi-monde" and the supposed "concierge", and with their disdain for the more conservative lifestyle of the upper class. Proust describes them as "the 'little nucleus' or 'little group' or 'little clan'," and they do make up their own society, with their own set of rules and hierarchy, and it's a group that would not be allowed to join the larger salons of higher French society. Disdain=jealousy?

Pages 265-269 are a richly comedic and ironic introduction to the "little set" of the Verdurins. Mme Verdurin declares that all other houses (salons) are boring, but at her own she keeps a tight reign over even what music can be played, evening dress is not allowed, and there "was never any programme for the evening's entertainment" (p.266). But for claiming so blasé an attitude, really Mme Verdurin is afraid of losing her "faithfuls" and this drives her to extremes. If I knew more about French society I might say that the Verdurin set was a caricature of the larger salons.

In a bit of foreshadowing, we are told that outsiders were allowed in only after being given a sort of test, and that "if he failed to pass, the faithful one who had introduced him would be taken on one side, and would be tactfully assisted to break with the friend or lover or mistress" (p.268)

We learn a lot more of Swann's character, mainly that he frequents, or at least is welcome in, the high society of the Faubourge Saint-Germain to which none of the Verdurin clan would be admitted, and that he is attracted to lower class women. Swann himself seems to be a dichotomy of good manners and vulgarity, since he is loved by so many and has been adopted by the nobility, yet is drawn to the lower classes, has no respect for class divisions, and has no scruples about asking for indecent favors from decent people.

Swann's taste in women appears to be exactly opposite his taste in art, "for the physical qualities which he instinctively sought were the direct opposite of those he admired in the women painted or sculpted by his favourite masters" (p.271). Again with the time, memory, art, and perception; a real person brings with them additional assaults on the senses and will alter perception even of physical beauty ("even in the most insignificant details of our daily life, none of us can be said to constitute a material whole, which is identical for everyone" [p.23], see notes p.35-58), something which is illustrated well with Odette.

Odette, as we've already heard, is one step away from being a demi-monde. She is well dressed and lives life as she wishes, she is a faithful in the bohemian circle of the Verdurins. According to the notes in my book her speech in the original is peppered with phrases written in English, such as "fishing for compliments" on p.269, and when she refers to Swann as "smart" and mentions his "home" on p.276. In my printing these phrases are in italics.

When Swann meets Odette he does not immediately find her attractive, so for someone who picks his mistresses based entirely on their looks she is an odd choice. This brings to mind the discussion of reading versus living, and the stages of removal from the senses in order to achieve ideal perception versus perception of the truth (pp.110-121). Something is always in the way of our knowing the truth about anything—ourselves.

M blames Swann's odd choice on his stage of life at the moment of meeting Odette, a "time of life, tinged already with disenchantment" (p.277), because at this stage, in looking for love, "we come to its aid, we falsify it by memory and by suggestion. Recognising one of its symptoms, we remember and re-create the rest." (p.277). He is creating his own reality, and that give credence to Proust's search for lost time, because if we are different at different stages, then looking back at any moment in life our memories will be tainted by our current person and the effects that person has on our perceptions of those moments from our past. To really remember them we must go back and recapture them as they were.

Quotes

"If he was not going to play they talked, and one of the friends—usually the painter who was in favour there that year—would 'spin,' as M. Verdurin put it, ' a damned funny yarn that made 'em all split with laughter,' and especially Mme Verdurin, who had such an inveterate habit of taking literally the figurative descriptions of her emotions that Dr. Cottard (then a promising young practitioner) had once had to reset her jaw, which she has dislocated from laughing too much." (pp.266-267) Bring on the hilarity.

Cool stuff:

Vermeer of Delft, or Joannes Vermeer, was a 17th century Dutch painter who focused on domestic scenes from the middle class. No wonder, then, that he was a focus of Swann the art critic.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Swann's Way, Combray II, pp.251-265

These are the final pages in part I, Combray and they bring us almost full circle to the narrator's thoughts at the beginning of the work, as though backing out from the more focused view to the more general one at the beginning.

After seeing Mme Guermantes in the church M returns to lamenting his impotence as a writer. He is afraid that he has no talent for his chosen profession and can find nothing to write about. It isn't until a return trip from a walk along the Guermantes Way that his writers block is broken and he writes a snippet on steeples in his view (the steeples of which he writes, not of Combray, are a trio—originally just two, and then a third attempts joins them—bringing to my mind the social triangle). He is relieved to be able to write again. It is a writer's epiphany.

He finishes the description of the Guermantes Way by linking it to feelings of "melancholy" because on nights they take that route, being late after such a long walk his mother is not free to come put him to bed. This is a break in the night-time routine upon which his happiness is dependent. The Guremantes Way embodies the dichotomy between utter happiness and desperate melancholy.

Some meandering thoughts...

I see another difference between the walks now, too, the first (Méséglise or Swann's Way) being connected more with sensuality, the second (Guermantes) with his intellectual (and social?) pursuit, or at least that's how they were depicted in his descriptions. Méséglise is sensual, lower class, country, French, stormy. Guermantes is intellectual, upper class or nobility. So while the Méséglise Way is a confirmation of all that is French and home, the Guremantes Way is what separates him from home and mother and comfort.

And then we're out in his more vague memories and ideas again, with a reminder of the madeleine cake and tea, and a preface to the upcoming memory, "a story which, many years after I had left the little place, had been told me of a love affair in which Swann had been involved before I was born" (p.262).

And finally we leave his sleep walking mind through the same door by which we had entered it, only instead of his confusion over which room he is half asleep in, now the room's true features are coming into focus with day. He is awake and memory is dawning?

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Review: His Dark Materials triology, by Philip Pullman (a review of sorts)

Setting all issues and agendas aside, this is a beautifully written young adult sci-fi story. I found myself falling in love with Lyra and her friends right from the beginning of this tale. Like many series I enjoyed the first book the most, but unlike others my interest had not seriously waned by the very last sentence, and now that I've finished I'm even looking into reading Pullman's additional works with these characters. They seemed so authentic, so believable, even in a universe acceptable only via suspension of disbelief, that I just fell in love with them each immediately.

Setting all issues and agendas aside, this is a beautifully written young adult sci-fi story. I found myself falling in love with Lyra and her friends right from the beginning of this tale. Like many series I enjoyed the first book the most, but unlike others my interest had not seriously waned by the very last sentence, and now that I've finished I'm even looking into reading Pullman's additional works with these characters. They seemed so authentic, so believable, even in a universe acceptable only via suspension of disbelief, that I just fell in love with them each immediately. The scenes, the suspense, the characters—all were rich and imagination grabbing throughout. The series is a calling together of many a myth and many a mystical culture, all given a physical meaning and existence. It is the story of an orphan who finds she has a purpose, and family, as she travels through an earth that is mostly foreign to us. Her journey is full of honor, magic, and love, and as she progresses we see her beginning to grow up. There is witchcraft, quantum mechanics, religion, death, sensuality. There is war, Armageddon style. There is love, there is a coming of age, but what could have become sappy or uncomfortable was written with sensitivity and authenticity so that it never crossed that line. The story is woven tightly and well, and it never let me drift away.

It has been said that Pullman's story is just shy of propaganda—the atheist's C. S. Lewis I think I've read—and with each successive book a message does become more obvious. It is with sharp literary skill that he doles out revelations of the symbolism and understory in carefully measured amounts. The final book is the most clear in terms of agenda, and not everyone will be comfortable with it, and The Golden Compass could conceivably be read as a stand alone, albeit with a rather plot hanging ending.

Books 28, 29, and 30 on my way to 52 in 2011

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

The Time Machine, by H. G. Wells (a review of sorts)

I am not a big reader of science fiction, and haven't had much of an introduction to nineteenth century science fiction. I picked up this book because I've always been curious about Wells, and after reading The Map of Time I thought now was as good a time as any to discover him. At just over a hundred small pages, it's a quick read, but there's a lot packed in, namely imagery and symbolism revealing the social stresses of a time when industrial advances were forcing the issue between socialism and capitalism. Though written in symbolism the social commentary is so obvious as to be almost distracting, and the hero makes so many leaps in his mental discovery that the story is increasingly discredited. But Wells is offering a good, light story, too, quick to read and enjoyable as just that—a brief story. In addition, reading it now felt almost like a sci-fi rite of iconic passage, and I'm glad I did it.

I am not a big reader of science fiction, and haven't had much of an introduction to nineteenth century science fiction. I picked up this book because I've always been curious about Wells, and after reading The Map of Time I thought now was as good a time as any to discover him. At just over a hundred small pages, it's a quick read, but there's a lot packed in, namely imagery and symbolism revealing the social stresses of a time when industrial advances were forcing the issue between socialism and capitalism. Though written in symbolism the social commentary is so obvious as to be almost distracting, and the hero makes so many leaps in his mental discovery that the story is increasingly discredited. But Wells is offering a good, light story, too, quick to read and enjoyable as just that—a brief story. In addition, reading it now felt almost like a sci-fi rite of iconic passage, and I'm glad I did it. Book 27 on my way to 52

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Swann's Way, Combray II, pp.233-251: Guermantes Way,

"The vertiginous spiral of Proust's metaphor presents the very substance of the Combray memory (the grandmother's artistic prejudice) as the spiral mental structure ensuring its own perpetuation, through transformation into a more lasting aesthetic form" (p.56, Proust in Venice)Compare to the moment a little later on (p.236) when he is called by the ruins of old battlements to imagine Combray as "an historic city vastly different, gripping my imagination by the remote, incomprehensible features which it half-concealed beneath a spangled veil of buttercups", most specifically remote, half-concealed images. These ruins have not been preserved and he can only imagine them as they were, or take them now as they are, overrun by nature.

We are now traveling with M along the Guermantes way. It is strikingly different from the Méséglise way almost immediately: descriptions of the Méséglise way include peasant girls and general, wild landscapes, while the Guermantes way brings to M's mind "the rumble of the coaches of the Duchesses ode Montpensier, de Guermantes and de Montmorency" (p.234) and also the various counts and lords and abbots of long ago (p.236). And where the Méséglise way seems practically pornographic, or at least bawdy, by comparison the Guermantes way seems clean and refreshing with its views of THE steeple and the Vivonne (Loire).

Neurasthenia (p.238) is an archaic psychiatric diagnosis of nervous exhaustion. It was often associated with the upper classes, and was possibly psychosomatic. On p.238 M mentions it with reference to Léonie, but Proust is said to have had neurasthenia (see The Diseases of Marcel Proust in Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, Part 2, by Bogousslavsky and Hennerici) and I'm starting to see a parallel drawn between them. When he mentions the illness it is with a desire to shake it, a feeling of helplessness, and later he says, of the Vivonne, "how often have I watched, and longed to imitate when I should be free to live as I chose" (p.240) giving a picture of a man who felt trapped in a sick body (which could be the asthma and neurasthenia, or could be the homosexuality, as viewed during that time).

M has two goals he wishes to reach along this walk: the source of the Vivonne, and Guermantes, itself, for a view of the noble family. The ancestry of the Guermantes family, is equally as impossible to find, but M attributes it to the legendary Geneviéve de Brabant (of the magic Lantern) and Gilbert the Bad, who, being legends, are timeless. He sees them in the tapestry and windows at the church of Combray, and it is at the church where he finally gets his first glimpse of the real Mme de Guermantes. He is disappointed, of course. She is too like a normal woman. But he reminds himself of her legendary heritage and looks for signs of her nobility and perfection, which of course he finds, and he "fell in love with her" and plants in his mind a connection between them, believing that she saw him and will think on him later.

Passages of note:

"satisfied with their modest horizon, rejoicing in the sunshine and the water's edge, faithful to their little glimpse of the railway-station, yet keeping none the less like some of our old paintings, in their plebeian simplicity, a poetic scintillation from the golden East." (p.237) he's talking about buttercups in the field, but I can't help noticing the railway-station reference, which I feel has some sort of significance in the work. Or maybe it doesn't.

Cool stuff:

Eugéne Viollet-le-Duc was the French architectural antithesis of John Ruskin. While Ruskin advocated restoration of buildings to their original states, Viollet-le-Duc restored buildings to a finished state, not caring whether they still resembled themselves at that point or not. Proust was a fan of Ruskin.

Gentile Bellini's Procession in St. Mark's Square

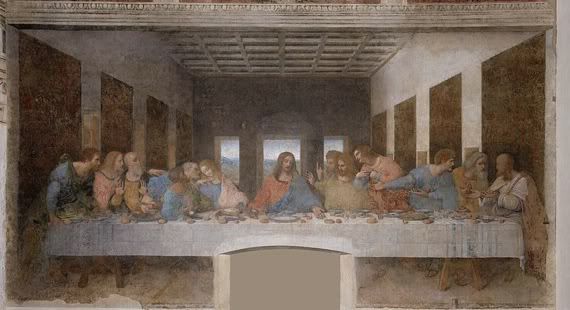

And of course DaVinci's The Last Supper

Thursday, August 4, 2011

Swann's Way, Combray II, pp.211-233:Méséglise: sensuality, sadism, and guilt

Several pages here are a description of Méséglise and reference to Roussainville. Méséglise is the walk that corresponds more to regular French life (as opposed to high society the Guermantes way). Proust gives us deep descriptions of the nature and architecture of the walk (of the church of Saint-André-des-Champs he says "how French that church was!" [p.212]) He describes for us the carvings of the church, relating them to the people of Françoise and Théodore (both of the lower French classes), and also to the "country-women of those parts" (p.213). The people, the countryside, the architecture are all immeasurably French.

Years have passed. Léonie has died and M is allowed to walk by himself while his parents handle her estate. If he was innocent or naive when he met Gilberte in the pink Hawthorns, he is now "in touch with" his sensuality ("my imagination drawing strength from contact with my sensuality, my sensuality expanding through all the realms of my imagination, my desire no longer had any bounds" [p.220]), and he seeks its fulfillment on this walk, looking for girls to hold behind every tree and ruin, but mostly in Roiussainville "into which I had long desired to penetrate," (p.220).

He begs Roussainville to send him a girl (from what I imagine to be a phallic "castle-keep" rising from the landscape) while he masturbates (for the first time) in his room at Combray.

"I could see nothing but its tower framed in the half-opened window as, with the heroic misgivings of a traveller setting out on a voyage of exploration or of a desperate wretch hesitating on the verge of self-destruction, faint with emotion, I explored, across the bounds of my own experience, an untrodden path which for all I knew was deadly—until the moment when a natural trail like that left by a snail smeared the leaves of hte flowering currant that drooped around me." (pp.222-223)It's even better in the purely Moncreif translation:

"...an untrodden path which, I believed, might lead me to my death, even—until passion spent itself and left me shuddering among the sprays of flowering currant which, creeping in through the window, tumbled all about my body." (p.217 volume I, Chatto & Windus uniform edition)But before these particular descriptions (of sensuality and masturbation) we are told that our narrator is now of age, but not yet disillusioned (pp.221-222), which is an intermediate step between the innocence of the earlier encounter with Gilberte in the hawthorns and the even that follows at Montjouvain.

Coming upon Montjouvain, the house of M. Venteuil, on one of these solo walks M witnesses a scene between Venteuil's newly bereaved daughter and her lesbian lover. He refers to this as the incident that formed his impression of sadism. Though he's talked about homosexuality before (in reference to the same girl), this would be his first witnessing of it, and here again a picture is drawn of homosexuality being a divide between the daughter and her father; she brings shame to his house and his memory, her willingness to take part in the affair is like spitting on his image.

But M is still certain that her father would have continued to love her, would have continued to see the good in her, and I can't help but hear a parallel between this and relationship Proust believed he had with his own family. At the same time he is certain that she wishes she could be different, or at least escape her connection to the good of her father, but she is too like him, and I wonder if here he (Proust) talks about himself, or if it is a reference to M's guilt over the masturbation, or both. Mlle Venteuil's, or M's, or Proust's, the guilt is there.

"It was not evil that gave her the idea of pleasure, that seemed to her attractive; it was pleasure, rather, that seemed evil. And as, each time she indulged in it, it was accompanied by evil thoughts such as ordinarily had no place in her virtuous mind, she came at length to see in pleasure itself something diabolical, to identify with Evil." (p.232)

Cool stuff:

An article about the different translations

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Swann's Way, Combray II, pp.204-211: M. Vinteuil and homosexuality

M. Vinteuil, whose daughter is a lesbian, has a house along the Méséglise Way. Proust himself was a closeted homosexual, but he has written his narrator as heterosexual, an arrangement that will allow Proust to explore the place of homosexuality in a wider social context.

Here the reference to homosexuality is with regards to parental shame, ruin, and death. But while society blamed the daughter for her father's death (due, they said, to a broken heart), they also admitted that M. Venteuil continued to love his daughter very much, even allowing her supposed lover to live in their home. This would seem to make society, and its harsh judgement, actually to blame for Venteuil's demise.

"And yet however much M. Vinteuil may have known of his daughter's conduct it did not follow that his adoration of her grew any less." (pp.208-209)

"But when M. Vinteuil thought of his daughter and himself from the point of view of society, fromt he point of view of their reputation, when he attempted to place himself by her side in the rank which they occupied in the general estimation of their neighbours, when he was bound to give judgment, to utter his own and her social condemnation in precisely the same terms as the most hostile inhabitant of Combary; he saw himself and his daughter in the lowest depths, and his manners had of late been tinged with that humility, that respect for persons who ranked above him and to whom he now looked up" (p.209)There may also be a comparison drawn here between the fall of M. Vinteuil, due to his daughter being a lesbian, and the fall of Swann, due to his chosen wife being of dubious morals. Both have been cast out by a judgmental society.

Notable passages:

"On my right I could see across the cornfields the two chiselled rustic spires of Saint-André-des-Champs, themselves as tapering, scaly, chequered, honeycombed, yellowing and friable as two ears of wheat." (p.205) This makes me think of Proust's love for Ruskin, and Ruskin's fourth tenet, the one regarding beauty which says that architecture should draw from or reflect nature (post).

Cool stuff:

Xavier Boniface Saintine (p.206) was an 19th century French writer.

Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre (p.206) was a Swiss artist who spent much of his life in France. The piece to which M refers is probably Lost Illusions, with the moon "silhouetted against the sky in the form of a silver sickle."