"The vertiginous spiral of Proust's metaphor presents the very substance of the Combray memory (the grandmother's artistic prejudice) as the spiral mental structure ensuring its own perpetuation, through transformation into a more lasting aesthetic form" (p.56, Proust in Venice)Compare to the moment a little later on (p.236) when he is called by the ruins of old battlements to imagine Combray as "an historic city vastly different, gripping my imagination by the remote, incomprehensible features which it half-concealed beneath a spangled veil of buttercups", most specifically remote, half-concealed images. These ruins have not been preserved and he can only imagine them as they were, or take them now as they are, overrun by nature.

We are now traveling with M along the Guermantes way. It is strikingly different from the Méséglise way almost immediately: descriptions of the Méséglise way include peasant girls and general, wild landscapes, while the Guermantes way brings to M's mind "the rumble of the coaches of the Duchesses ode Montpensier, de Guermantes and de Montmorency" (p.234) and also the various counts and lords and abbots of long ago (p.236). And where the Méséglise way seems practically pornographic, or at least bawdy, by comparison the Guermantes way seems clean and refreshing with its views of THE steeple and the Vivonne (Loire).

Neurasthenia (p.238) is an archaic psychiatric diagnosis of nervous exhaustion. It was often associated with the upper classes, and was possibly psychosomatic. On p.238 M mentions it with reference to Léonie, but Proust is said to have had neurasthenia (see The Diseases of Marcel Proust in Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, Part 2, by Bogousslavsky and Hennerici) and I'm starting to see a parallel drawn between them. When he mentions the illness it is with a desire to shake it, a feeling of helplessness, and later he says, of the Vivonne, "how often have I watched, and longed to imitate when I should be free to live as I chose" (p.240) giving a picture of a man who felt trapped in a sick body (which could be the asthma and neurasthenia, or could be the homosexuality, as viewed during that time).

M has two goals he wishes to reach along this walk: the source of the Vivonne, and Guermantes, itself, for a view of the noble family. The ancestry of the Guermantes family, is equally as impossible to find, but M attributes it to the legendary Geneviéve de Brabant (of the magic Lantern) and Gilbert the Bad, who, being legends, are timeless. He sees them in the tapestry and windows at the church of Combray, and it is at the church where he finally gets his first glimpse of the real Mme de Guermantes. He is disappointed, of course. She is too like a normal woman. But he reminds himself of her legendary heritage and looks for signs of her nobility and perfection, which of course he finds, and he "fell in love with her" and plants in his mind a connection between them, believing that she saw him and will think on him later.

Passages of note:

"satisfied with their modest horizon, rejoicing in the sunshine and the water's edge, faithful to their little glimpse of the railway-station, yet keeping none the less like some of our old paintings, in their plebeian simplicity, a poetic scintillation from the golden East." (p.237) he's talking about buttercups in the field, but I can't help noticing the railway-station reference, which I feel has some sort of significance in the work. Or maybe it doesn't.

Cool stuff:

Eugéne Viollet-le-Duc was the French architectural antithesis of John Ruskin. While Ruskin advocated restoration of buildings to their original states, Viollet-le-Duc restored buildings to a finished state, not caring whether they still resembled themselves at that point or not. Proust was a fan of Ruskin.

Gentile Bellini's Procession in St. Mark's Square

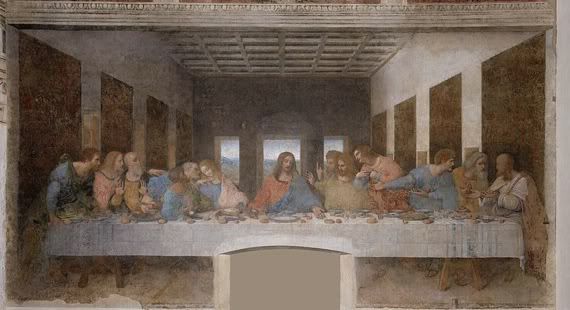

And of course DaVinci's The Last Supper