Beginning with the first sentence of Part Two,

Swann in Love

I want to love everything about this work, but with this section I am at a loss. Since all the rest of the work so far feels justified, based on the truth of memories and the seeking of them, the transition to this section, which is the retelling of a story once told to our narrator, feels rather awkward to me. The story within a story has never been one of my favorite literary styles or tools, and I can only hope that the remainder of the work does not feel this clumsy.

The Verdurins and their friends are described a little later as being "

among the riff-raff of Bohemia" (p.281), which is fitting with their patronage of the artist and pianist, with their acceptance of the "

demi-monde" and the supposed "

concierge", and with their disdain for the more conservative lifestyle of the upper class. Proust describes them as "the 'little nucleus' or 'little group' or 'little clan'," and they do make up their own society, with their own set of rules and hierarchy, and it's a group that would not be allowed to join the larger

salons of higher French society. Disdain=jealousy?

Pages 265-269 are a richly comedic and ironic introduction to the "

little set" of the Verdurins. Mme Verdurin declares that all other houses (salons) are boring, but at her own she keeps a tight reign over even what music can be played, evening dress is not allowed, and there "

was never any programme for the evening's entertainment" (p.266). But for claiming so blasé an attitude, really Mme Verdurin is afraid of losing her "faithfuls" and this drives her to extremes. If I knew more about French society I might say that the Verdurin set was a caricature of the larger salons.

In a bit of foreshadowing, we are told that outsiders were allowed in only after being given a sort of test, and that "

if he failed to pass, the faithful one who had introduced him would be taken on one side, and would be tactfully assisted to break with the friend or lover or mistress" (p.268)

We learn a lot more of

Swann's character, mainly that he frequents, or at least is welcome in, the high society of the

Faubourge Saint-Germain to which none of the Verdurin clan would be admitted, and that he is attracted to lower class women. Swann himself seems to be a dichotomy of good manners and vulgarity, since he is loved by so many and has been adopted by the nobility, yet is drawn to the lower classes, has no respect for class divisions, and has no scruples about asking for indecent favors from decent people.

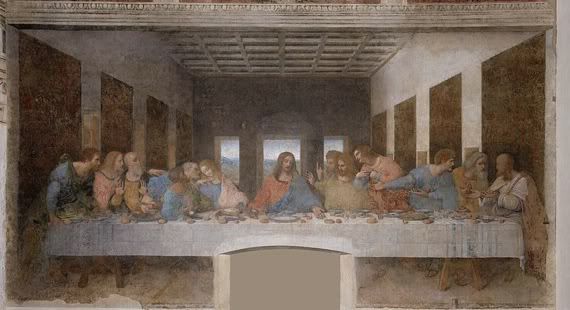

Swann's taste in women appears to be exactly opposite his taste in art, "

for the physical qualities which he instinctively sought were the direct opposite of those he admired in the women painted or sculpted by his favourite masters" (p.271). Again with the

time, memory, art, and perception; a real person brings with them additional assaults on the senses and will alter perception even of physical beauty ("

even in the most insignificant details of our daily life, none of us can be said to constitute a material whole, which is identical for everyone" [p.23], see notes

p.35-58), something which is illustrated well with Odette.

Odette, as we've already heard, is one step away from being a demi-monde. She is well dressed and lives life as she wishes, she is a faithful in the bohemian circle of the Verdurins. According to the notes in my book her speech in the original is peppered with phrases written in English, such as "

fishing for compliments" on p.269, and when she refers to Swann as "

smart" and mentions his "

home" on p.276. In my printing these phrases are in italics.

When

Swann meets Odette he does not immediately find her attractive, so for someone who picks his mistresses based entirely on their looks she is an odd choice. This brings to mind the discussion of reading versus living, and the stages of removal from the senses in order to achieve ideal perception versus perception of the truth (

pp.110-121). Something is always in the way of our knowing the truth about anything—ourselves.

M blames Swann's odd choice on his stage of life at the moment of meeting Odette, a "

time of life, tinged already with disenchantment" (p.277), because at this stage, in looking for love, "

we come to its aid, we falsify it by memory and by suggestion. Recognising one of its symptoms, we remember and re-create the rest." (p.277). He is creating his own reality, and that give credence to

Proust's search for lost time, because if we are different at different stages, then looking back at any moment in life our memories will be tainted by our current person and the effects that person has on our perceptions of those moments from our past. To really remember them we must go back and recapture them as they were.

Quotes

"

If he was not going to play they talked, and one of the friends—usually the painter who was in favour there that year—would 'spin,' as M. Verdurin put it, ' a damned funny yarn that made 'em all split with laughter,' and especially Mme Verdurin, who had such an inveterate habit of taking literally the figurative descriptions of her emotions that Dr. Cottard (then a promising young practitioner) had once had to reset her jaw, which she has dislocated from laughing too much." (pp.266-267) Bring on the hilarity.

Cool stuff:

Vermeer of Delft, or Joannes Vermeer, was a 17th century Dutch painter who focused on domestic scenes from the middle class. No wonder, then, that he was a focus of Swann the art critic.

The

Kay Scarpetta series is my guilty pleasure. My book candy. It has no

seriously redeeming value, but I have always enjoyed the characters. As

it seems to be with all series, the first books were the best, and her

2010 release left much to be desired, so I was a little apprehensive

about the newest book, Red Mist, which came out on Tuesday. Actually,

though, this newest additon to the series was a return to many of the

things I loved in her earlier books. Scarpetta is in South Carolina for

this one, looking further into the death of her deputy chief Fielding.

There is plenty in this episode that harks back to the previous one, but

our old Scarpetta is back—clear thinking and organized. All our usual

characters are here as well, and we get our triumphant ending. There are

some slow parts, and the book seems to take a while to get started, but

Cornwell's writing is familiar once again, and the story is enjoyable.

The

Kay Scarpetta series is my guilty pleasure. My book candy. It has no

seriously redeeming value, but I have always enjoyed the characters. As

it seems to be with all series, the first books were the best, and her

2010 release left much to be desired, so I was a little apprehensive

about the newest book, Red Mist, which came out on Tuesday. Actually,

though, this newest additon to the series was a return to many of the

things I loved in her earlier books. Scarpetta is in South Carolina for

this one, looking further into the death of her deputy chief Fielding.

There is plenty in this episode that harks back to the previous one, but

our old Scarpetta is back—clear thinking and organized. All our usual

characters are here as well, and we get our triumphant ending. There are

some slow parts, and the book seems to take a while to get started, but

Cornwell's writing is familiar once again, and the story is enjoyable.